After the German capitulation, many Dutch

people came out on the streets waving Dutch flags – this could be very

dangerous as there were still armed Germans everywhere. The following morning we went into action; I put

on my gear and went into action. I went

into the barracks, a large former children’s home with a big courtyard, and was

surprised to see the results. Some

people must have got this place ready, right under the noses of the

Germans. There were at least 200 bunk

beds, guns, helmets and ammunition.

There was also a Guard Room, a cycle repair shop, first aid post and

kitchen.

Young members of the Binnenlandsche Strijdkrachten.

Egbert is third to the right of the man with the Sten gun

©Egbert Hughes

Not all Germans surrendered immediately and

groups of SS troops were still giving trouble and so the Commanding Officer

sent men to guard the road blocks and to prevent any rogue troops from coming

back into the town and barricading themselves into buildings, causing more

casualties.

ID Card as Dispatcher for the emergency

evacuation of Gouda as the German Army

had flooded large areas to delay the Allies

©Egbert Hughes

I and another fellow were sent to a road near

Reeuwijk to stop any Germans trying to get back into town. We took up positions behind a concrete

anti-tank barrier, from where we could see the advancing Allies (probably the

Canadians) on the High Road, some distance away. Suddenly a small German motorised column

appeared from under the viaduct and began to advance in our direction. We fired several warning shots and the

Germans replied with a salvo of Spandau machine gun fire which scattered

concrete chippings in all directions.

The Allies heard the commotion and rushed to

the scene where they dealt with the renegade Germans. A Canadian Jeep with a Sergeant manning a

Bren gun came to a halt beside us; they thanked us and told us to go home. We reported the incident to our C.O. when we

returned to the barracks.

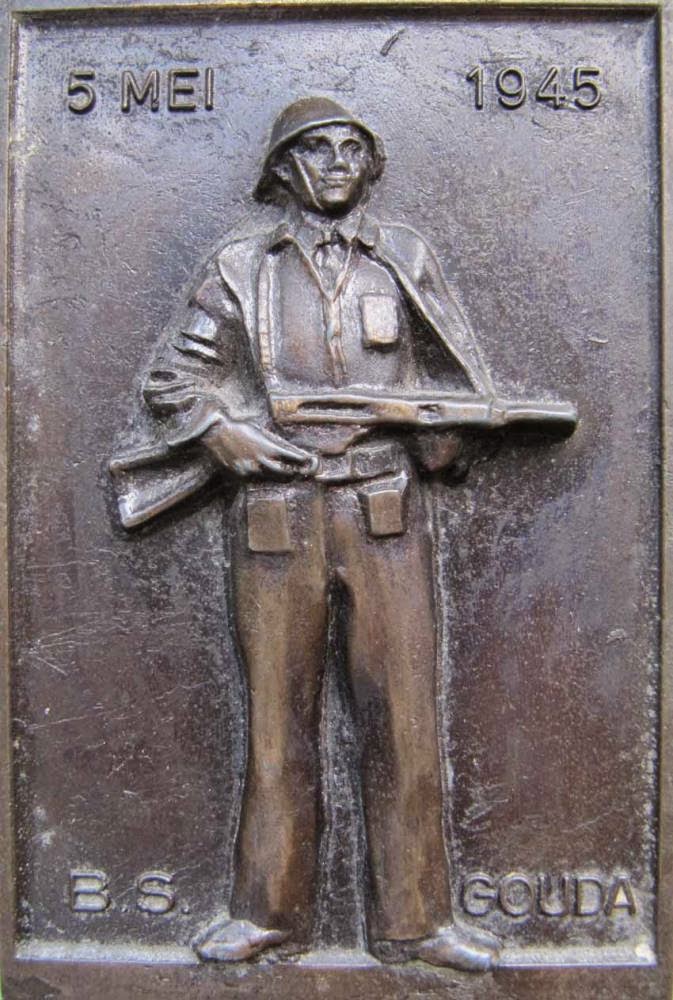

Gouda Interior Forces Bronze Plaque

Origin unknown

One evening, I was detailed guard duties and

found that I was to be responsible for a candle lit cellar containing nine

German prisoners. They were probably SS

and members of a Deathshead group; they were very dangerous men just waiting

for interrogation and I was glad when my shift was over.

On the Sunday morning we went to Scheveningen

dunes near The Hague where many officers were meeting and we had to stand

outside and guard the marquees. Although

it was May, it was cold and wet and I was shivering. An Officer handed me a glass of whisky

through the tent flaps and said that it would warm me up.

After a few weeks, our duties were coming to

an end and after handing in my ID, sten gun and armband, I took on the job of

an armed guard for the Canadian garrison.

They gave me a German made machine pistol and the food was

excellent! After they left, I became an

assistant with 67 Forward Main Store Section, British Army of the Rhine. Under

Captain Larkin, who was also the military town Mayor.

At one of his cocktail parties I met a German

Jew named Hugo Kahn and his son Helmut (the rest of the family perished in

concentration camps) and they offered me a job in their newly founded instrument

factory, mainly making drawing instruments.

After working there for several months, I was

called to the office, where I was confronted by a very rude man from the

Ministry of Labour. He told me that I

had no right to work in Holland without a work permit. I lost my temper, I was very angry indeed and

he left, saying that he would be back that afternoon. Indeed, he returned with a female Immigration

Officer and they decided that, as an alien, I would be deported.

I was taken to their Head Office, where I was

seen by the Head of Department. He was a

very nice elderly official; he looked through my Passport and found the letter

from HRH Prince Bernhardt thanking me for my efforts during the war. He returned my passport and said that my

deportation order was officially cancelled.

He wrote a letter and told me to go to Rotterdam and sign on as a ship’s

steward. I did just that but they told

me that I could not be considered for the job because I was British not Dutch.

On my way home, at the railway station, I

picked up an English newspaper in which I saw that the RAF were looking for

engineers. When I told my mother that I

would like to join the Royal Air Force, she was all for it. She bought me a ferry ticket from the Hook of

Holland to Harwich and gave me £5 – which was the maximum permitted at the

time. I packed a wicker suitcase and, on

28th February 1947, I set off for dear old Blighty

and endured a very rough crossing to Harwich.

This was the end of

an era and the start of a new one.

During my time in Holland two Gouda men died in battle; eighteen

Resistance fighters were shot by the Germans; another eighteen did not return

from prison and forty five people were killed in bombing raids. Several hundred Jews perished in

concentration camps; sixty people did not return from forced labour camps in

Germany; hundreds died of cold and hunger and we were bombed six times between

25th February 1941 and November 1944. The railway was heavily bombed as it was the

main junction for trains from Germany to The Hague and Rotterdam and many

nurses were killed when the RAF bombed the hospital.

No comments:

Post a Comment