SPECIAL PEOPLE (WHO WERE NOT PART OF 304 SQUADRON) WITH STORIES THAT HAVE TO BE TOLD

Wednesday, 1 October 2014

THE VERY BEGINNINGS

INTRODUCTION

Part of the philosophy of Blitzkrieg is that

there is no need to declare war; this gives the aggressor the tactical

advantage whilst the build up to it is a psychological assault on the nerves of

the victims. In the same twisted system

of logic, the fact that the nations under attack are declared neutrals is

immaterial. And this is how an Anglo-Dutch family was dragged into the Second

World War.

On the morning of 10th May 1940,

German forces moved into the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. Their intention was to draw the French and

the British Expeditionary forces deep into Belgium, away from the Ardennes and

the airfields on the Dutch coast which the Luftwaffe needed as a springboard to

attack England and to harass Allied shipping in the English Channel.

The Dutch Forces were little more than a nominal defence force with no tanks, few artillery pieces and only limited numbers of armoured cars andhe word. The Dutch Air Force was limited to only about 140 antiquated aircraft, almost half of which were destroyed on the first day of the invasion.

The German assault was rapid but it met with considerable

resistance. The Hague was well, and

courageously, defended against an assault by German paratroops, foiling the

German attempt to seize the Dutch Government in the initial attack and heavy

casualties were inflicted on the German troops who tried to seize the airfields

at Ypenburg and Ockenburg. But, stiff as

the resistance was, the Dutch were ill equipped and unprepared to take on the

might of Nazi Germany. Queen Wilhelmina

and her Government escaped to England, where they set up a Government in Exile.

In Rotterdam, up to 900 civilians were killed and 25,000 houses were destroyed in the bombing which had been concentrated on homes rather than defences or military targets. Whilst negotiations for surrender were going on, the Luftwaffe bombed the city heavily, resulting in the previously mentioned carnage. The Germans had an easy victory – but there was still resistance.

© Bundesarchiv,

Bild 146-1969-097-17 / Hausen, v. / CC-BY-SA

His father, Edward Gerard Hughes, was born in Whitehaven, Cumberland (now

Cumbria) in 1878 and his mother, Margaretha Stijns-Hughes, was born in

Maastricht, Holland in 1888. They were connected

to the bulb growing industry in Spalding, Lincolnshire and travelled frequently

to Holland. In fact two of their four

children were born there.

Edward Gerard Hughes

Margaretha Stijns-Hughes

Egbert himself was born on 27th

October 1926 at No 12 Het Amerikaantje (meaning the little American Indian) in

Gouda, Holland and was delivered by his Dutch Grandmother; he was the youngest

of the four. They moved to No 1 which

was known as “The Point” as the house was on a sharp corner about fifty metres

from the River Ijsel, where it was an active port with landing stages for the

barges. They lived right opposite the

Schuttelaar coffee roasting plant and loved the deliciously overpowering aroma.

They lived right over a Kroeg (pub) but a

very busy one that was frequented by sailors and was very rowdy on a Saturday

night. Of course Egbert had no memory of

that. When he was three years old, his

father went out to buy some tobacco and was never seen again, leaving his

mother with four children and very little money. There were no benefits in those days but

there was a charity which handed out food to the needy and they relied quite

heavily on it.

They moved to a single storey rented property

which had a garden and a ditch which led into a lake; he and his brother Ted

had a raft which they floated down to the lake and spent their time swimming

and fishing.

Later they moved to another house close to

where Egbert was born and he seems to have had a happy childhood enjoying all

the usual pastimes and sports with a normal group of friends.

In the dark days immediately before the

outbreak of World War II, the British Consul advised his mother to return to

England where the family would be relatively safe from the uncertainty caused

by the looming clouds of war. However,

she believed that Holland would remain neutral – as they had done during the Great

War.

In Egbert’s words: the Germans put paid to

that idea as they invaded Holland in May 1940 and rounded up all the

undesirable aliens (in this case British subjects). This meant that his brother John was arrested

and taken away to a transit camp at Schoorl in Northern Holland and on to a

prison camp near Breslau in Poland where he spent the rest of the war.

Egbert and his other brother Ted were told

that they would receive the same treatment when they were old enough under the

terms of the Geneva Convention. However,

they spent the rest of the war dodging the Gestapo and becoming part of a young

Resistance group known as “For Netherlands’ Freedom” and later as part of the

Interior Battle Forces which became very active after the failure of Operation

Market Garden and the Arnhem debacle.

Egbert received a

Certificate, a Resistance Badge and a letter of thanks from Prince Bernhard for

his activities during his time in the Resistance.

Letter of thanks from Prins Bernhard

Certificate of Service in the Dutch

Binnenlandsche Strijdkrachten

(Interior Forces, which were the

formalisation of the Dutch Resistance)

Badge received by all members of the Resistance

Medals were not awarded

Photos © Egbert Hughes unless otherwise stated

EGBERT "DUTCHIE" HUGHES - A LIFE AT WAR

The following story is as told to me by

Egbert “Dutchie” Hughes and represents his personal memories, as told to me,

from birth to the end of the War:

Reporting the news to the British People

The London Evening Standard - 10th May 1940

Image© London Evening Standard

On the morning of 10th May 1940, I was awoken

by the drone of heavy bombers and the rattle of machine gun fire. This could only be dog-fighting between the

modern German fighters and the antiquated Royal Dutch Air Force in their

ancient bi-planes. I later learned that

65 of the 140 strong Dutch Air Force planes had been destroyed on this first

day of fighting.

I looked out of the window and noticed a lot

of Dutch military activity; I got dressed and went down to speak to the

soldiers and ask them what was happening. They told me that Germany had invaded The Netherlands and that heavy

fighting was going on in some areas.

German paratroops had landed in all the strategic areas such as the

Ports, airfields and even the grounds of the Royal Palace in The Hague. However, the Royal Family had already fled to

England, via Zeeland, and would establish a Government in Exile there.

After five days of heavy fighting, the Dutch

Military authorities decided to surrender because of the heavy loss of life

that had already taken place and to prevent any further unnecessary bloodshed. On 15th May 1940, General Henri Winkelman

signed the Dutch Capitulation documents.

However, this was not before the Luftwaffe received the order to stop

bombing and Rotterdam received a serious pounding and many civilians and Dutch

and German troops were killed in the fighting.

During the fighting, the sky was filled with

smoke and the smell of burning paper; the sky was full of bits of burning

paper. Thousands of people fled from the

battle areas, mainly on bicycles, and escapees from the burning city of

Rotterdam gravitated towards Gouda. My

mother took in 19 refugees; the ladies slept in our beds and the remainder –

including us – slept on the floor.

The next morning, a Dutch Army vehicle

stopped outside our door. I went to see

and it was laden with soldiers, all in a state of shock, one of them was crying

and shaking like a leaf. I got a glass

of water and held it to his lips, but he was shaking so much, he spilled most

of it and his teeth were rattling against the glass – I don’t know what

happened to them.

A few days later, I was standing on the

pavement and heard the sound of a heavy vehicle; I saw a German tank come

round the corner, with many marching soldiers singing their marching

songs. I took an instant dislike to

their jackboots and their awful helmets.

They came to a halt and started knocking on doors asking for their water

bottles to be filled. I think they had

been told to be friendly towards the Dutch people, because they were not

hostile.

They went on and assembled in the Market

Place; some of them started to take over buildings such as schools and

warehouses, and the Officer in charge settled himself in the Hotel de Zalm in

the Market Square. The Germans wasted no

time in exerting their authority – posters and signposts appeared everywhere,

telling us that the penalty for disobeying German orders would be death.

German propaganda poster urging Dutchmen to join their forces

Failed because of the superior German attitude towards the Dutch

At some point, after the invasion, I returned

to school, but one day a German teacher arrived – probably to promulgate some

German propaganda – and I made my resentment noticeable. I decided to leave school and took a day

course in engineering at the Technical College; later, I changed to evening

classes but this soon became impossible because of the curfew imposed by the

Germans.

Map showing Gouda (top right) in the direct invasion line to Rotterdam

It did not take long for the Germans to round

up all the Foreign Nationals and, early one morning, they came and took my two

brothers away – giving them time only to pack a bag. They told me that I would be next, as soon as

I was old enough. Ted and John were

taken to an Internment Camp at Schoorl, in Northern Holland in transit to a

camp near Breslau in Poland. John spent

the next five years there, but Ted was released with the warning that he would

also be sent there in due course.

This was not to happen as we spent the next

few years dodging the Germans. John had

been the bread winner and so we had been deprived of a source of income. I decided to apply for a job with a company

who made buses for the Dutch Railways. I

reported to the foreman who told me that I had to pass a test before I could be

employed.

He took me to a long bench, fitted with

several vices holding a long drive shaft and he gave me a scriber, a long metal

ruler, a centre punch, a hammer and a cross-cut chisel. My task was to make an oil groove along the

length of the drive shaft. I spent three

days on this test and suffered a bloody left thumb but the foreman was pleased

with the result and I got the job.

My first job was bending the tubular steel to

make the frames for the seating on the buses and later, to make the fittings

that would be necessary for the proper working of the automatic doors. Very shortly afterwards, the Germans took

over the factory to manufacture and repair military vehicles.

I thought it a good idea to slow down the

progress on the German vehicles, if I could, and I saw an opportunity to start

a one man saboteur action. I could trust

all my workmates except the doorkeeper and so I had to be wary of him. One of my better moves was to damage a

machine tool which would take two months to replace. Another way of slowing them down was to alter

the measurements on some of their drawings so that the finished components

would be too big or too small to be of use – delaying their progress again.

Welding was a major part of the construction

process, but the welders only had an oxygen bottle on their trolleys and the

acetylene had to be accessed from a plant outside via valves around the

site. I was responsible for maintenance

of the plant and for the correct mixture of calcium carbide and water in the

acetylene supply. This was another

opportunity to delay production by increasing the amount of calcium carbide in

the water. The plant walls were made of

compressed straw in case of an explosion, and that is just what they got. Mind you, I was the one who had to repair the

damage and get the acetylene supply going again! It soon became obvious that I would be in

serious trouble if the Gestapo became suspicious – especially being a Brit. I hate to think what they would have done to

me.

I had to jack in the

job, even though this would mean there was no money coming in again. However, help was at hand; one day, a

gentleman from the International Red Cross came to see us and told us that he

was able to offer the British citizens a monthly loan so that they were not

forced to work for the enemy. My brother

and I quickly accepted this offer, which had to be repaid after the war –

although we were never asked to repay it.

It was a life saver and I have no idea how they organised it with a War

on.

EARLY RESISTANCE

One day, I received a Post Office Giro

envelope containing a note asking me to meet someone at a house in town. My curiosity got the better of me and I

went. On arrival at the house, I found

the door ajar and I went in. The place

was empty and I went upstairs and, in the front bedroom, I found a Bible on a

table. As I looked at it, a man appeared

in the doorway; he seemed to know all about me and, in conversation, he asked

me if I was interested in joining a resistance group to perform tasks that

would release more mature men from some of the minor jobs. I agreed and he told me I would have to swear

allegiance to Queen Wilhelmina. He then

told me to go home and I would be contacted if and when required.

The jobs we had to do were cleaning guns,

manning road blocks and observation posts to note German movements in and out

of town, weapons training and instruction in street fighting.

As the War went on, food became harder to

get, so sometimes I would get on my bike and cycle into the countryside to buy

milk from the farms. On one such

occasion, on my return home along a narrow dyke, I was confronted by a German

armoured vehicle. I had nowhere to go

and no choice but to stop. The Officer,

in a grey leather coat, held up his hand to stop me. I was searched but was carrying nothing

suspicious, so my personal items were returned to me, although they kept my

papers and the soldiers took three of my six bottles of milk.

The vehicle had broken down and they had no

radio communications so the Officer gave me a note and an address in Gouda to

get assistance. I hated to do it but I

had no choice as he had my papers and my name and address. The following morning a gefreiter (corporal)

came to the house and brought my papers back with two cigarettes. None of the family smoked, so they ended up

in the dustbin.

Ted and I had several safe houses, around the

town, where we stayed at times; one of mine was a sweet shop run by a lady with

three daughters. Her husband had been

taken away by the Germans and sent to a camp somewhere in Germany. One of her daughters worked in the hospital

which had both Allied and German wounded servicemen as patients. I used to collect her from the hospital and

often chatted with our wounded (and also with the German wounded, to avoid

suspicion) whilst I waited for her.

On one occasion, on the way home, we were

walking down a dark, tree lined lane (just after curfew). We heard the marching footsteps of a German

patrol. We stood close to the dark fence

of a coal yard, in the hope that they would not see us. Unfortunately we were seen and they took us

to an office in a warehouse where we were guarded by two members of the feld

gendarmerie, armed with machine pistols.

I held her hand to steady her.

A young SS Officer entered the room with a

female interpreter; he sat down and she stood beside him. She was looking at me as if she knew me –

quite possible as Gouda was a small place at the time. She was probably at school with me.

The Officer was holding my ID card; he did

not notice the two red lines and the word “Vreemdeling” meaning foreigner. The girl did see it and she looked at me as

if to say “You are in trouble”. He asked

me the same questions several times as if he was trying to trick me into giving

a different answer. He asked me why I

had to escort the girl home from the hospital and he got angry when I asked him

if he would let his daughter walk home through a town full of enemy soldiers.

He told me I was old enough to go to Germany

to help with the war effort but first I would be taken to the Gestapo. That would be fatal as they would have found

out that I was British – and God knows what they would have had in store for

me. We were escorted outside and ordered

onto a half track, when the interpreter started a heated argument with the

Officer (maybe she was his girlfriend).

I do not know what she said to him but he ordered us down from the half

track, gave us a very strong warning and told us to go. That lady most probably saved my life; we ran

and ran and, with hearts beating like a drum, made it to the house.

There was another incident when I was

standing on the pavement and two other fellows were talking a little further on

and two ladies were standing behind me chatting. A German vehicle came past and stopped at the

corner of the street by a large building which accommodated German

Officers. A podgy, middle aged Officer

came around the corner and ordered us to go with him. He must have noticed I was missing because he

came back around the corner and shouted to come here. I did not move.

Egbert (centre) with friends Henk and Jan

Taken in Gouda in 1942

They, and the Gestapo, had no idea he was British!

©Egbert Hughes

He came up to me and drew his gun and I was

looking straight down the barrel of a 9mm Luger. He said: “Come, you have to work!” I replied, in German, that I do not work for

the enemy, to which he said that they had been here for three years and we were

all Germans, now.

I said that maybe all those people, but not

me because I am British. He was still

pointing the gun at me and I was astonished when he told me to prove it. I gave him my British passport and he clearly

did not read English or Dutch but, as he flipped through the pages, he must

have noticed the word Police on the permit to reside in Holland because he said

it was in order, holstered his gun, clicked his heels and walked away. I think I had really tried my luck that time.

In September 1944 the Resistance put us on

standby for an Allied invasion and potential action in support of them. This was the event later filmed as “A Bridge

Too Far” where the Allies failed to capture the bridge at Arnhem and the

invasion failed. As a result of this we

were stood down and that part of Holland was not liberated until May 1945 – at

the very end of the war.

By now, the times were very hard for

civilians and occupying armies alike.

Everything was in very short supply and the shops were empty. Keeping warm was a problem too; there was no

gas, water, electricity, water, fire wood, coal, paper or candles. My mother made up a bowl of water with a

little oil floating on the top; a small square of very thin metal with a hole

in it held a piece of candle wick.

Together they made up a very feeble light.

With the onset of autumn, the weather became very cold

and there were heavy falls of snow, which made matters worse. Ted and I used to go to bed at 4pm, just to

keep warm. By December, there were

people starving and dying of the cold and it became known as the Hunger Winter.

THE HUNGER WINTER

To ease the situation at home, I decided to

make for a safe house in the country. I

strapped my kitbag onto my bike and waited for a moonlit night before setting

off on my perilous journey. It was a bit

hair-raising, the front tyre sliding all over the place in the snow. It was not a proper tyre; it was made from

the solid rubber of an old lorry tyre, held together at the ends by a strong

piece of wire.

I pedalled out of town along a minor road,

passing the German Military Police Headquarters, on the way. They were not out and about in the cold and

snow, but I could hear them singing as I cycled past.

After going up a small hill, the road

intersected with the main road and ran alongside a canal, right opposite the

bridge I had to cross. A sentry came out

of his box and shouted “Werda!” meaning who goes there? At that same moment a German motorcyclist

appeared and the sentry turned his attention to him. I saw my chance and pedalled past at high

speed across the bridge.

There was another sentry at the other end of

the bridge and he must have thought I had been checked out because he waved and

shouted “Gruss Gott”. He must have been

an Austrian conscript and I answered him with the same greeting and cycled on

to enter the village of Waddinxveen and then turned right along a dyke. I reached my destination and slid down the

dyke with my bike.

I knocked on the door of a cottage and a

big dark shape of a woman let me in; she brought my bike in and then led me up

a flight of bare wooden stairs. She told

me so find a place on the floor against the wall. I wrapped myself in my blanket for warmth but

in no time I felt like I was being bitten all over – the place was infested

with fleas.

As dawn broke, I noticed several faces peering

over the side of a crib and they suddenly jumped out of it and left the

room. Shortly afterwards, the woman

appeared from an adjoining room and with her there were three little girls;

they also went out of the room. As it

got lighter, I looked at the boys’ crib; it was filled with straw, smelled

heavily of urine (they must all have been bed-wetters) and was crawling with

fleas – the source of my overnight discomfort.

I made my way downstairs and, as I reached

the ground floor, I noticed that the front window was missing and there was

snow everywhere. It was sparsely

furnished and had a sideboard with its doors hanging off and clothes hanging

out. I learned that they never washed

their clothes but when they could no longer wear them they simply put on new

ones. The woman worked for local farmers who all gave her the cast off clothing

of their own kids.

I walked along a corridor at the end of which

was a scullery, also with a broken window and with snow lying around and piled

up against the wall. I entered the

living room, which was full of dirty looking kids, and the eldest boy – whom I

called Piet – told me that the large stove was still warm, but they had no more

wood. I told him that we must get more

wood or we would all die of hypothermia.

Piet and I went down the meadows and found

some deserted trenches, shored up by wood.

We dismantled a substantial amount of it and made four trips each

carrying it back to the house. In no

time, the stove was burning again and the room was nice and warm.

Piet’s younger brother had long hair and a

filthy face so I decided to spruce him up a bit. I filled a bucket with snow and heated it

over the stove, resulting in half a bucket of warm water. I cut his hair and thoroughly washed his

face; he looked really good and when his mother came home she hardly recognised

him!

Piet told me that his Grandparents had a

smallholding not far away and he was worried about his Grandfather. Apparently they had had a blazing row and, in

the argument, his Grandmother had lost the sight in one eye. They never spoke again and he was banished

from the house to the barn. Piet asked

me to go with him to check up on his Grandfather. As we entered the barn, the awful smell hit

me; I didn’t need a doctor to tell me that this was the putrescent smell of

gangrene. The old man was wrapped in a couple of old coats and his feet were

covered in wet sacking. I told Piet that

we had to get his Grandfather to hospital as he was in a very poor state.

We hastened back to the house and I wrote a

note asking for urgent help. I waited on

the top of the dyke and several people walked past. I stopped a young girl and asked if she was

going to Gouda; she said that she was and so I asked her if she would deliver

the note to the Red Cross Station. She

did deliver it and, the next day, two women arrived with a makeshift stretcher

suspended on a frame between bicycle wheels.

We took them to the barn, where they put on

masks and lifted the old man onto the stretcher then set off on the long

journey back to town. We heard later

that he had had both legs amputated but he had not been strong enough to

withstand the shock and he had died.

Piet was very upset at the news.

For all the hardships and lack of hygiene,

Piet’s mother managed to get a supply of food from the farmers she worked for

and we never went too hungry.

By the beginning of 1945, the bombing of

Germany increased and we saw many bombers passing over on their way to deliver

their deadly load. One day, as we were

watching the bomber stream, hundreds of them, passing overhead, a man standing

near me – probably a Nazi sympathiser shook his fist in the air and said that

if he ever got his hands on an Englishman, he would kill him. Little did he

know that he was standing next to one!

The time had come for me to return to Gouda,

but the Germans were very active in the area and were checking the papers of

everyone at the bridge so it was difficult for me. Piet’s mother was very brave; she got on her bike

and did a reconnaissance along the canal.

She returned and told me that she had arranged with a farmer to row me

across the canal away from the bridge.

He was brave too as it would probably have meant facing a firing squad

if he had been caught with an Englishman in his boat. So, I made my farewells and Piet Was very

sorry to see me go.

Once across the canal, I had no trouble

getting to Gouda and, apart from a Group of Germans on the corner of my street

who just looked at me, I was home. My

mother was surprised to see me and said that she didn’t know how she was going

to feed me.

The big anthracite stove was gone and in its

place was a small, round stove on which was a little pan with a white substance

in it. I asked my Mother what it was and

she told me that it was something the Germans had issued and it was even

difficult to mix with water. The bread

rations were meagre, the slices of brown bread were very small indeed.

Starvation was taking a hold and Queen

Wilhelmina asked Churchill, Montgomery and Eisenhower to do an emergency food

drop to the people of Holland. They were

reluctant to do so as the aircraft would have to fly very low indeed. Eventually, an agreement was made with the

Germans, the local commanders agreed not to fire on the aircraft providing they

flew along strictly demarcated corridors and were unarmed. As a result, many tons of food were dropped

and the Germans honoured their agreement.

One man was killed after being hit by a container and movement of the

food was very slow due to the lack of transport – but it was a beginning. Operation Manna saved many lives in Holland

during those closing days of the war.

©New York Times

2nd May 1945

British aircraft delivered 6,680 tons of food to Holland

(including Gouda) as part of Operation Manna and the Americans delivered about

4,000 tons as part of Operation Chowhound.

This was almost immediately followed by Operation Faust in which 200

lorries were used to deliver food to Rhenen which was also behind German

lines. The grateful Dutch people spelled

out a message in Tulips! which could be read from the air; it said “MANY

THANKS”.

A typical food drop during Operation Manna

Food, Peace, Freedom - a locally produced plaque

Giving thanks for the food drop of Operation Manna

and looking forward to peace - only days away

FINAL DAYS OF WAR - AND THE AFTERMATH

After the German capitulation, many Dutch

people came out on the streets waving Dutch flags – this could be very

dangerous as there were still armed Germans everywhere. The following morning we went into action; I put

on my gear and went into action. I went

into the barracks, a large former children’s home with a big courtyard, and was

surprised to see the results. Some

people must have got this place ready, right under the noses of the

Germans. There were at least 200 bunk

beds, guns, helmets and ammunition.

There was also a Guard Room, a cycle repair shop, first aid post and

kitchen.

Young members of the Binnenlandsche Strijdkrachten.

Egbert is third to the right of the man with the Sten gun

©Egbert Hughes

Not all Germans surrendered immediately and

groups of SS troops were still giving trouble and so the Commanding Officer

sent men to guard the road blocks and to prevent any rogue troops from coming

back into the town and barricading themselves into buildings, causing more

casualties.

ID Card as Dispatcher for the emergency

evacuation of Gouda as the German Army

had flooded large areas to delay the Allies

©Egbert Hughes

I and another fellow were sent to a road near

Reeuwijk to stop any Germans trying to get back into town. We took up positions behind a concrete

anti-tank barrier, from where we could see the advancing Allies (probably the

Canadians) on the High Road, some distance away. Suddenly a small German motorised column

appeared from under the viaduct and began to advance in our direction. We fired several warning shots and the

Germans replied with a salvo of Spandau machine gun fire which scattered

concrete chippings in all directions.

The Allies heard the commotion and rushed to

the scene where they dealt with the renegade Germans. A Canadian Jeep with a Sergeant manning a

Bren gun came to a halt beside us; they thanked us and told us to go home. We reported the incident to our C.O. when we

returned to the barracks.

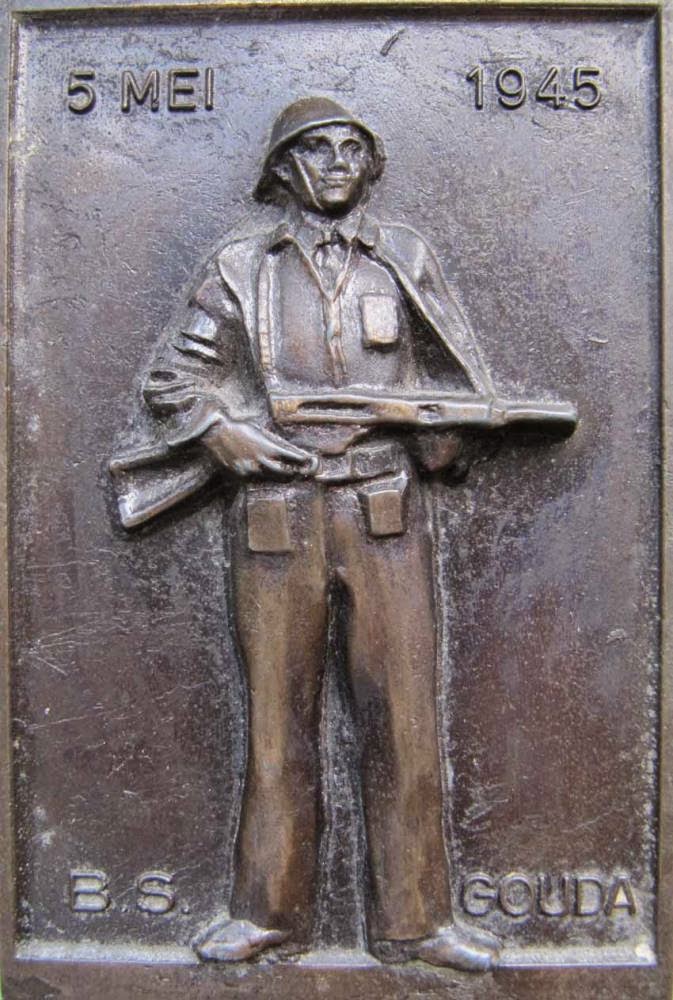

Gouda Interior Forces Bronze Plaque

Origin unknown

One evening, I was detailed guard duties and

found that I was to be responsible for a candle lit cellar containing nine

German prisoners. They were probably SS

and members of a Deathshead group; they were very dangerous men just waiting

for interrogation and I was glad when my shift was over.

On the Sunday morning we went to Scheveningen

dunes near The Hague where many officers were meeting and we had to stand

outside and guard the marquees. Although

it was May, it was cold and wet and I was shivering. An Officer handed me a glass of whisky

through the tent flaps and said that it would warm me up.

After a few weeks, our duties were coming to

an end and after handing in my ID, sten gun and armband, I took on the job of

an armed guard for the Canadian garrison.

They gave me a German made machine pistol and the food was

excellent! After they left, I became an

assistant with 67 Forward Main Store Section, British Army of the Rhine. Under

Captain Larkin, who was also the military town Mayor.

At one of his cocktail parties I met a German

Jew named Hugo Kahn and his son Helmut (the rest of the family perished in

concentration camps) and they offered me a job in their newly founded instrument

factory, mainly making drawing instruments.

After working there for several months, I was

called to the office, where I was confronted by a very rude man from the

Ministry of Labour. He told me that I

had no right to work in Holland without a work permit. I lost my temper, I was very angry indeed and

he left, saying that he would be back that afternoon. Indeed, he returned with a female Immigration

Officer and they decided that, as an alien, I would be deported.

I was taken to their Head Office, where I was

seen by the Head of Department. He was a

very nice elderly official; he looked through my Passport and found the letter

from HRH Prince Bernhardt thanking me for my efforts during the war. He returned my passport and said that my

deportation order was officially cancelled.

He wrote a letter and told me to go to Rotterdam and sign on as a ship’s

steward. I did just that but they told

me that I could not be considered for the job because I was British not Dutch.

On my way home, at the railway station, I

picked up an English newspaper in which I saw that the RAF were looking for

engineers. When I told my mother that I

would like to join the Royal Air Force, she was all for it. She bought me a ferry ticket from the Hook of

Holland to Harwich and gave me £5 – which was the maximum permitted at the

time. I packed a wicker suitcase and, on

28th February 1947, I set off for dear old Blighty

and endured a very rough crossing to Harwich.

This was the end of

an era and the start of a new one.

During my time in Holland two Gouda men died in battle; eighteen

Resistance fighters were shot by the Germans; another eighteen did not return

from prison and forty five people were killed in bombing raids. Several hundred Jews perished in

concentration camps; sixty people did not return from forced labour camps in

Germany; hundreds died of cold and hunger and we were bombed six times between

25th February 1941 and November 1944. The railway was heavily bombed as it was the

main junction for trains from Germany to The Hague and Rotterdam and many

nurses were killed when the RAF bombed the hospital.

A NEW ERA IN THE RAF

After arriving at Harwich, I made my way to

Euston Station in London and then on to Lime Street Station in Liverpool. I was hoping to meet my brother John but he

was not there so I just had to wait as I did not know where he lived. Hours later, he appeared and took me to a

Chinese restaurant where he ordered a rice dish for us. I did not know how to use chopsticks so the

waiter went to a neighbouring restaurant and borrowed cutlery for me to use!

Afterwards, we went to his digs and he asked about renting a room for me. The landlord allowed me to stay in an army bed in the attic, rent free, and during the day I stayed in John’s room.

The following day, I went to get my ration books and was given a double ration when I told them where I had come from. After that I went to the RAF recruiting office and was offered a job as a coppersmith and sheet metal worker. Shortly afterwards I was sent for a medical, which I passed with ease and, a few days later, I received a travel warrant to take me to No 1 School of Recruit Training at RAF Cardington in Bedfordshire.

I arrived there on 9th April 1947

and was kitted out, sworn in and we had our group photograph taken. Following this, my group was posted to RAF

Bridgenorth, Shropshire where I was known as AC2 Hughes, Egbert 4023355. This was where I did my basic military

training.

First Group Photo in the RAF (April 1947) - Egbert is second from left in the front row

On the rifle range, we had to fire a Sten gun

from the hip and from the shoulder; a sergeant stood beside me and was

surprised that I hit the target both times.

He said that the Sten was a difficult and dangerous gun to fire and he

almost believed that I had fired one before.

I told him that I had, during the war, but I think he thought I was

lying.

Some of the Officers and NCOs were obnoxious

to the new recruits and could be cruel at times. The basic examples ranged from silly to

downright nasty; I had to sign a form saying that lack of knowledge of the

English language was not an excuse to disobey an order. On another occasion I was having a smoke

beside a grass covered air raid shelter when an Officer and a sergeant

approached my group and ordered us to remove our boots and socks. Those whose nails were too long were made to

file their nails down with large files the sergeant handed out. I always kept my nails short and the Officer

instructed the sergeant to give me the bayonet treatment. This involved sticking a bayonet in the

ground and making me hold my finger on the end while the sergeant turned me

round and round then made me stand up. I

was dizzy and fell down like a drunk amid loud laughter.

On another occasion, on church parade, the

Warrant Officer called for all Roman Catholics and Jews to fall out. We did not know that the parade was only for

Church of England airmen but we waited by the edge of the parade ground. As I passed the sergeant he whispered “March

smart, you bloody Jew!” I was trembling

with anger.

After the parade I went to the Orderly Room

and filed my complaint with the Station Adjutant. He went in to speak to the Wing Commander who

called me in and asked why I was so angry and upset. I explained that some of my family’s Jewish

friends had perished in the gas chambers and that was the reason for my

anger. I was dismissed and the sergeant

was presumably reprimanded.

More than likely so as he called me out to

fall in for lunch one day and when I went out he took me to the armoury where

he signed out a Short Magazine Lee Enfield rifle. He ordered me to raise it above my head and

run around the parade square. In no

time, my arms were screaming with pain; however, it came to an abrupt end. The C.O. must have watched it all from his

office window as he came out and shouted me over; he told me to sign the rifle

back in and then go for lunch and he would deal with it. I have no idea what happened but I had no

more trouble from that NCO.

After we passed out, I was posted to RAF

Keevil near Trowbridge in Wiltshire. I

arrived at Trowbridge Station late at night and there was not a soul about

except a Warrant Officer who gave me a lift in his taxi and dropped me at the

gates of the airfield gates. There was

only an LAC on duty in the Guard Room and he gave me a cup of tea and told me

to sleep in one of the cells. In the

morning I reported to the Orderly Room where I was issued with a bicycle

(because my billet was down the road on a farm.

I also received a bayonet to be used on parade.

RAF Keevil, Steeple Ashton nr Trowbridge, Wiltshire

Ironically used as a despatch point for gliders sent on

Operation Market Garden (Arnhem) and on D-Day (France)

I went to the sheet metal shop and met Roy

Kirk, the LAC in charge. He was from

Dronfield near Chesterfield in Derbyshire and we got on just fine. Every month his wife sent him a cake and he

always shared it with me. The Station

was due to close and move to RAF Chivenor near Barnstaple in Devon so almost

everyone went home on leave, but some of us stayed behind to keep an eye on the

place.

One evening I went to the pub in Steeple

Ashton and asked for a pint of beer. The

barmaid told me they didn’t have any but offered me a pint of cider, which I

accepted and I joined the farm tractor driver.

I finished my pint and ordered another one and he warned me to take it

easy as it was powerful stuff. In

Holland, I thought that cider was low alcohol and I thought he was kidding me so I had a

third one. I did feel a bit funny and I

said cheerio to him and, as I hit the fresh air outside, I realised I was

drunk. I staggered all the way to my

billet, fell on to my bed and went to sleep still wearing my hat and coat.

I woke up staring at the light bulb hanging

from the ceiling; I looked at my watch and realised that I had overslept. I got ready and jumped on my bike and

pedalled to the airfield as fast as I could.

The rest of the boys were already lined up outside of the Orderly Room

and the Officer said:

“You are late, airman.”

He asked each of us if we had anything to

report and when he got to me he said:

“Airman, there are two red eyeballs staring

at me. Have you been on the Scrumpy last

night?”

I said that I had and he told me to go back

to my billet and sleep it off and be on guard tonight without fail.

The day came for the move to RAF Chivenor and

I went with a civilian driver and a truck load of spares. But my stay at Chivenor was to be a short

one.

I made some good friends there; one was

George Ferbrache he was a parachute packer and came from Guernsey. He always had his pockets full of Horlicks

tablets and boiled sweets nicked from the supply of emergency rations in the

stores.

27th October 1947 was my 21st

Birthday and I received no cards or presents but, whilst I was working on an

aircraft, my mate Michael Cartriss, who was from Cardiff, came up and wished me

a Happy Birthday from his sister Nancy.

He gave me a card and a Ronson lighter; a nice surprise from a girl I

didn’t even know. However, I went up to

Cardiff to meet her and we became firm friends.

George and I often went up to Cardiff for the weekend and stayed with her

parents. They were lovely people but we

lost touch after I moved on to another station.

Soon I moved to RAF Weeton near Blackpool and

on arrival I was allocated the Wing and Billet that was to be my home for the

next eighteen months. It was winter and

freezing and the accommodation had not been used since the end of World War

2. The boys in there had gone to an

empty billet and smashed up some wooden lockers to use as fuel to heat up the

place. The water system was completely

frozen up and the workmen were having no luck in putting it right. Meanwhile we could not have a shower, wash or

bath.

The Station Adjutant laid on transport and we

went off to the public baths in Blackpool.

It was absolute Heaven to soak in a hot bath. Over the weeks, things improved and we were

able to start our course – with civilian instructors.

I joined the Station sports team and on

Wednesdays we had Station sports days and on Saturdays we had cross

country. I took part in the 24 mile News

of the World Relay race in Bradford – we each did 4 miles and, after competing

we could still go into Blackpool. For a

shilling (5p) we could go to a variety show and then use the same ticket to go

dancing in the Tower Ballroom, mostly to Ted Heath and his band.

The Station Entertainment Officer would

organise dances and he would invite landladies and their daughters and friends

and even lay on transport for them. I

made friends with Mrs Farrant and she gave me a key to her Guest House and said

when you are in Blackpool, come and see me and if I’m not at home, help yourself

to food and drink. I was still in touch

with her up until about 1970.

As a result of my

work, I was taken into hospital with a painful and badly swollen chin. I had copper poisoning and had to have a lot

of penicillin injections. I felt sorry

for the nurses who had to dress that unpleasant area of infection – the doctor

remarked that they had caught the infection just in time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)