To ease the situation at home, I decided to

make for a safe house in the country. I

strapped my kitbag onto my bike and waited for a moonlit night before setting

off on my perilous journey. It was a bit

hair-raising, the front tyre sliding all over the place in the snow. It was not a proper tyre; it was made from

the solid rubber of an old lorry tyre, held together at the ends by a strong

piece of wire.

I pedalled out of town along a minor road,

passing the German Military Police Headquarters, on the way. They were not out and about in the cold and

snow, but I could hear them singing as I cycled past.

After going up a small hill, the road

intersected with the main road and ran alongside a canal, right opposite the

bridge I had to cross. A sentry came out

of his box and shouted “Werda!” meaning who goes there? At that same moment a German motorcyclist

appeared and the sentry turned his attention to him. I saw my chance and pedalled past at high

speed across the bridge.

There was another sentry at the other end of

the bridge and he must have thought I had been checked out because he waved and

shouted “Gruss Gott”. He must have been

an Austrian conscript and I answered him with the same greeting and cycled on

to enter the village of Waddinxveen and then turned right along a dyke. I reached my destination and slid down the

dyke with my bike.

I knocked on the door of a cottage and a

big dark shape of a woman let me in; she brought my bike in and then led me up

a flight of bare wooden stairs. She told

me so find a place on the floor against the wall. I wrapped myself in my blanket for warmth but

in no time I felt like I was being bitten all over – the place was infested

with fleas.

As dawn broke, I noticed several faces peering

over the side of a crib and they suddenly jumped out of it and left the

room. Shortly afterwards, the woman

appeared from an adjoining room and with her there were three little girls;

they also went out of the room. As it

got lighter, I looked at the boys’ crib; it was filled with straw, smelled

heavily of urine (they must all have been bed-wetters) and was crawling with

fleas – the source of my overnight discomfort.

I made my way downstairs and, as I reached

the ground floor, I noticed that the front window was missing and there was

snow everywhere. It was sparsely

furnished and had a sideboard with its doors hanging off and clothes hanging

out. I learned that they never washed

their clothes but when they could no longer wear them they simply put on new

ones. The woman worked for local farmers who all gave her the cast off clothing

of their own kids.

I walked along a corridor at the end of which

was a scullery, also with a broken window and with snow lying around and piled

up against the wall. I entered the

living room, which was full of dirty looking kids, and the eldest boy – whom I

called Piet – told me that the large stove was still warm, but they had no more

wood. I told him that we must get more

wood or we would all die of hypothermia.

Piet and I went down the meadows and found

some deserted trenches, shored up by wood.

We dismantled a substantial amount of it and made four trips each

carrying it back to the house. In no

time, the stove was burning again and the room was nice and warm.

Piet’s younger brother had long hair and a

filthy face so I decided to spruce him up a bit. I filled a bucket with snow and heated it

over the stove, resulting in half a bucket of warm water. I cut his hair and thoroughly washed his

face; he looked really good and when his mother came home she hardly recognised

him!

Piet told me that his Grandparents had a

smallholding not far away and he was worried about his Grandfather. Apparently they had had a blazing row and, in

the argument, his Grandmother had lost the sight in one eye. They never spoke again and he was banished

from the house to the barn. Piet asked

me to go with him to check up on his Grandfather. As we entered the barn, the awful smell hit

me; I didn’t need a doctor to tell me that this was the putrescent smell of

gangrene. The old man was wrapped in a couple of old coats and his feet were

covered in wet sacking. I told Piet that

we had to get his Grandfather to hospital as he was in a very poor state.

We hastened back to the house and I wrote a

note asking for urgent help. I waited on

the top of the dyke and several people walked past. I stopped a young girl and asked if she was

going to Gouda; she said that she was and so I asked her if she would deliver

the note to the Red Cross Station. She

did deliver it and, the next day, two women arrived with a makeshift stretcher

suspended on a frame between bicycle wheels.

We took them to the barn, where they put on

masks and lifted the old man onto the stretcher then set off on the long

journey back to town. We heard later

that he had had both legs amputated but he had not been strong enough to

withstand the shock and he had died.

Piet was very upset at the news.

For all the hardships and lack of hygiene,

Piet’s mother managed to get a supply of food from the farmers she worked for

and we never went too hungry.

By the beginning of 1945, the bombing of

Germany increased and we saw many bombers passing over on their way to deliver

their deadly load. One day, as we were

watching the bomber stream, hundreds of them, passing overhead, a man standing

near me – probably a Nazi sympathiser shook his fist in the air and said that

if he ever got his hands on an Englishman, he would kill him. Little did he

know that he was standing next to one!

The time had come for me to return to Gouda,

but the Germans were very active in the area and were checking the papers of

everyone at the bridge so it was difficult for me. Piet’s mother was very brave; she got on her bike

and did a reconnaissance along the canal.

She returned and told me that she had arranged with a farmer to row me

across the canal away from the bridge.

He was brave too as it would probably have meant facing a firing squad

if he had been caught with an Englishman in his boat. So, I made my farewells and Piet Was very

sorry to see me go.

Once across the canal, I had no trouble

getting to Gouda and, apart from a Group of Germans on the corner of my street

who just looked at me, I was home. My

mother was surprised to see me and said that she didn’t know how she was going

to feed me.

The big anthracite stove was gone and in its

place was a small, round stove on which was a little pan with a white substance

in it. I asked my Mother what it was and

she told me that it was something the Germans had issued and it was even

difficult to mix with water. The bread

rations were meagre, the slices of brown bread were very small indeed.

Starvation was taking a hold and Queen

Wilhelmina asked Churchill, Montgomery and Eisenhower to do an emergency food

drop to the people of Holland. They were

reluctant to do so as the aircraft would have to fly very low indeed. Eventually, an agreement was made with the

Germans, the local commanders agreed not to fire on the aircraft providing they

flew along strictly demarcated corridors and were unarmed. As a result, many tons of food were dropped

and the Germans honoured their agreement.

One man was killed after being hit by a container and movement of the

food was very slow due to the lack of transport – but it was a beginning. Operation Manna saved many lives in Holland

during those closing days of the war.

©New York Times

2nd May 1945

British aircraft delivered 6,680 tons of food to Holland

(including Gouda) as part of Operation Manna and the Americans delivered about

4,000 tons as part of Operation Chowhound.

This was almost immediately followed by Operation Faust in which 200

lorries were used to deliver food to Rhenen which was also behind German

lines. The grateful Dutch people spelled

out a message in Tulips! which could be read from the air; it said “MANY

THANKS”.

A typical food drop during Operation Manna

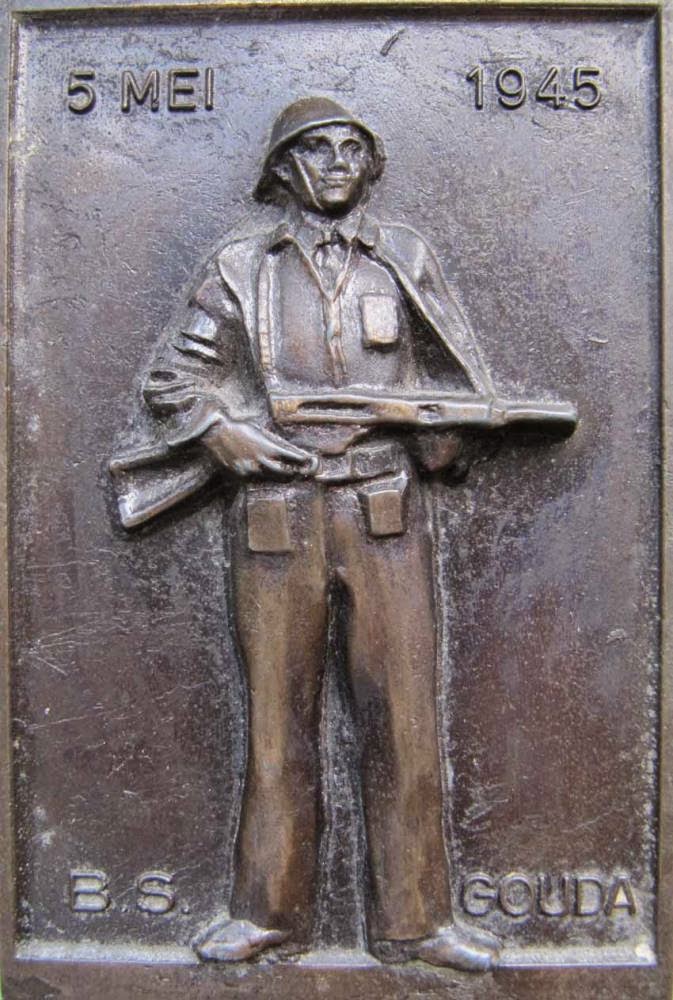

Food, Peace, Freedom - a locally produced plaque

Giving thanks for the food drop of Operation Manna

and looking forward to peace - only days away

.png)